Field Notes

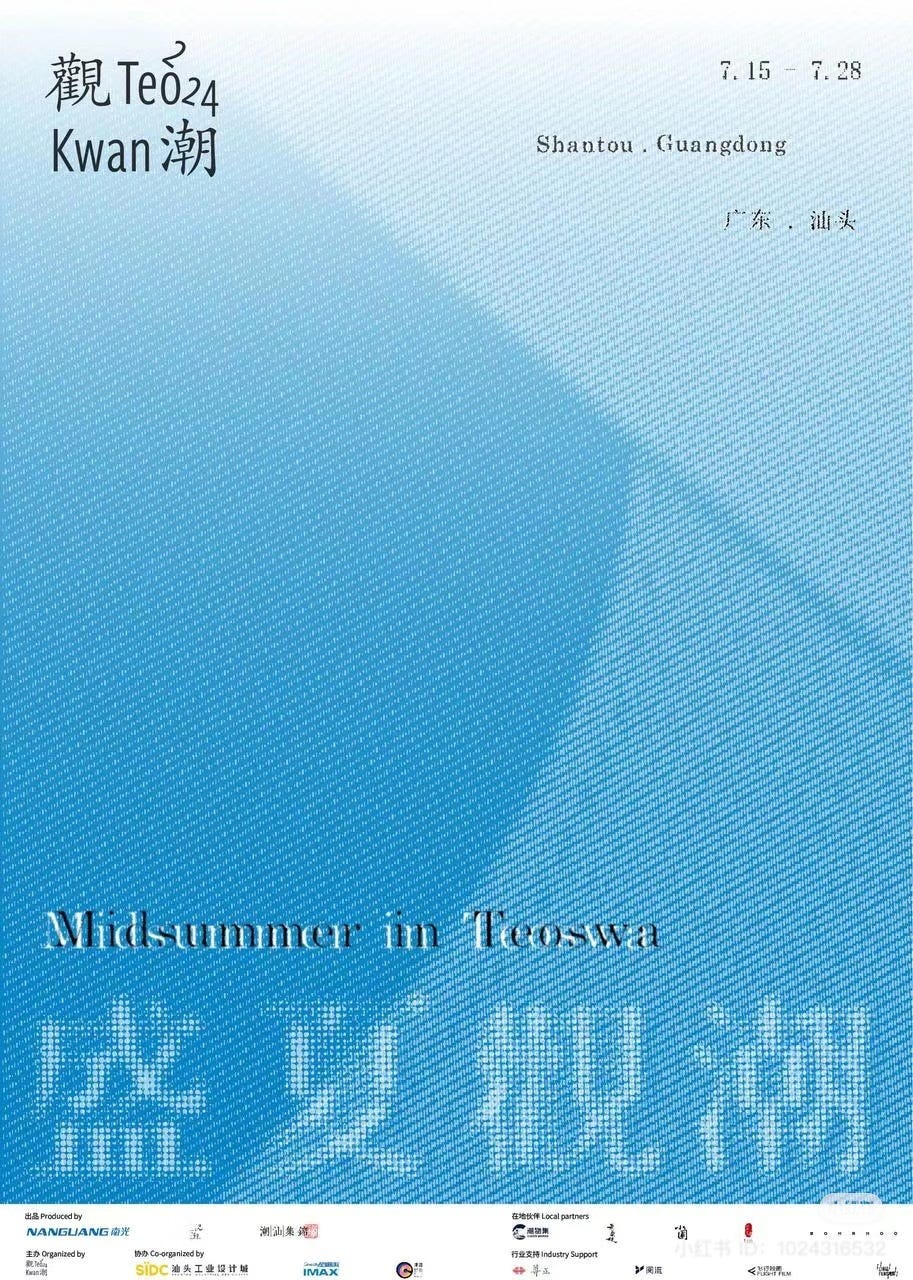

Malaysian director Edmund Yeo was visiting earlier this month and over lunch he mentioned that he was going to Shantou for a film festival. He had gone with his parents last year and taken the opportunity to visit his extended family for the first time (those who had not left the area in the many waves of migration). He showed me the program and I noticed various titles which did not have the longbiao — the Chinese censorship approval logo. How did they get away with it? “It's not a ‘film festival’” he explained. He introduced me to the organizers and in less than a week, I was on a train (also with my parents!) headed for Shantou for my very first visit.

Shantou is located three hours by high speed rail north-east of Hong Kong, on the coast. Along with Chaozhou and Jieyang, it is part of the cultural-linguistic region known as Chaoshan or Teoswa (潮汕). The language and people originating from the region are referred to as Teoswa or Teochew. My grandfather left the region for Hong Kong in the 1930s where he set up restaurants and a noodle factory serving Teochew cuisine.

After checking into the hotel, we went to have our first Shantou meal: beef hot pot.

Huang Ji’s Egg and Stone was screening that evening. I met up with Edmund and we milled about as we waited. 45 minutes past the start time, they finally started letting people in. The organisers and the director proceeded to explain that they had faced some technical problems, and they could not get the film’s sound to work.

Ji proceeded to explain the work involved in this sort of independent exhibition in China and how, usually, they would do a technical check before every screening to adjust the colours and volume. She and the organisers had been at it for over an hour, getting nowhere, so they decided to let us all in and show us how the sausage was made. The specifics still escape me, but it sounds like commercial cineplexes like this one now had restrictions on non-encrypted DCPs in an effort from above to further deter screening of non-commercial / films without government approval.

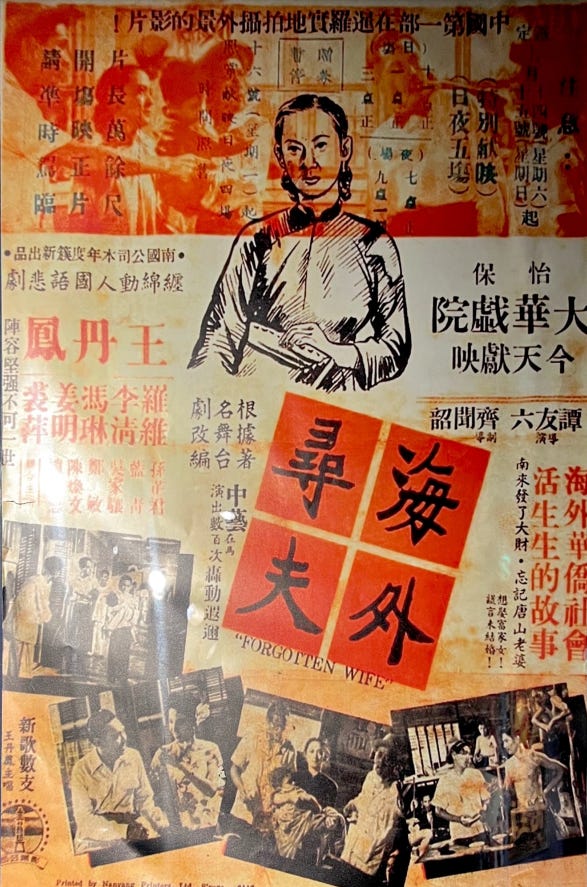

Some audience members suggested we skip directly to the Q&A session since the event had previously screened Ji’s other two films in the trilogy: Stonewalling & The Foolish Bird. In an attempt to stall for time, the programmer got up and began a promoting the upcoming events. The next evening was to be a screening of short films from local directors, and the evening after that was a 1950 film that is nearly impossible to see. My interest was immediately piqued. The film in question, Tam Yau Luk’s Forgotten Wife (海外尋夫) was shot on location in Thailand. It now stands as a document of the experience of Chaoshan laborers and society in Bangkok at the time. The programmer explained that the original producer, Nanguo Film Company, was a left-wing Hong Kong production company that had folded and sold its assets to a Guoqi (State-owned enterprise), which had then sold it to a Yangqi (Central government controlled enterprise). The elements were held at the Hong Kong Film Archives, while the restoration was completed by the China Film Archives. It had taken 3 years to negotiate this screening, and the last bout of conversations had taken 3 months.

Meanwhile Egg and Stone was still not working. “Alright,” he began, “let me begin advertising next week's events,”— then the sound came on, the room erupted in applause and the screening began. Later that night, I changed my train ticket and arranged to stay another night so I could see Forgotten Wife (1950).

Forgotten Wife stars Wang Danfeng as the titular wife Su-Zhen and Lo Wei (director of Fist of Fury) as her ingrate husband Pan A-Liu. The film begins with a send-off to the husband… except A-Liu is nowhere to be seen. When he finally saunters in, he explains that he had stopped to buy his favorite tea, introducing a recurring motif of Teochew gongfu tea. “There won’t be tea like this over there,” he says, as the camera focuses on the characteristically small earthen teapot, seemingly unaware of the life of labor he’s sailing towards. That night, along with A-Gang, another man from the village, A-Liu leaves his homeland to joins the rank of overseas labourers in South East Asia.

After A-Gang moves on to Sabah with a duck-farming cousin, Liu loses his last connection to home and spends all his time at the mahjong parlour. His tea brewing skills are noticed by the boss, and soon he's invited to pour for them at a teahouse. From then on, he's rechristened Pan Youcheng, further shedding his origins. The boss' daughter, Baofeng, spots his likeness to a movie star in her magazine, and very soon, he's the son-in-law to one of the richest Teochew merchants in the city. When the Japanese invade during World War II, the merchants rush to collaborate with them, seeing it as an opportunity to make more money. Brown-nosing makes Liu the richest Japanese collaborator in Bangkok, attracting jealousy he does nothing to mitigate. Soon, his allies, his girlfriend Anna, and his new wife Baofeng are scheming to grab his assets. Meanwhile, his forgotten wife and son begin the arduous, weeklong journey by boat to Bangkok to look for him. In the hull of the boat, without food and drink, a fellow traveller bemoans the conditions on his deathbed. This, as explained after the screening, was how many labourers traveled to Bangkok. Later Teochew-Singaporean director Sun Koh who was also attending the festival told me that’s literally how her dad left Chaoshan. On arrival, mother and son are met by a Teochew mutual aid society where Suzhen is reunited with A-Gang who takes her to confront A-Liu.

In lieu of a post-screening talk, the programmer opened up the floor to hear the audience’s feedback on the film. One audience member noted in the post-screening discussion that even from a contemporary feminist gaze, Forgotten Wife features three strong and independent female characters in captivating performances. When his wife Baofeng realises that A-Liu had been previously married, she demands her inheritance (which had gone to A-Liu when they married). When A-Liu’s true nature is revealed, his first wife Su-Zhen declares that she and her son will not starve as long as she has two hands to labour with. This trio of women are rounded off by the charming and fashionable girlfriend Anna who had known from the beginning that she was in it for the payday. She leaves him, with the majority of his money, and skips town to Singapore.

Another programmer spoke also about the concept of “home” and “away”– and that when asked “where are you from?” and “where are you going?” that the answer would rarely be China and South East Asia. Most of the Teochew migrants would say they were from Chaoshan and that they were guofan (過番)–going to a foreign place for economic reasons. In particular, this referred to economic migration to South East Asia, including Vietnam, Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, Philippines, Cambodia, and Laos which all have large Teochew populations and speakers to this day. Once in these new places, Teochew people would gather to form merchant associations, like the one A-Liu and his fellow merchants had to collaborate with the Japanese, and the Mutual Aid society A-Gang sets up to help new arrivals.

Forgotten Wife remains relevant as both a historical document of Teochew migration and diaspora and an example of the ambitious and entertaining left-wing cinema of the early 1950s. Teochew culture is significant throughout, with the recurring tea motif. Tea pouring gives A-Liu his start in Bangkok, and his teapot is broken at the end of the film by a furious Baofeng. Suzhen, who brought tea for A-Liu, leaves without giving it to him, signifying a continuation of this culture onto her son with or without his father. Meanwhile, diminishing dumplings, characteristic of Teochew cuisine, are used at one point to signify the passing of time. Though the Teochew dub of the film is now presumed lost, the Mandarin dubbed version retains the flavor through the food, tea, and social fabric associated with the Teochew diaspora.

Director Tam Yau Luk was born and raised in Shantou, and began directing in Shanghai in the 1930s. With the start of World War II, he moved, with the Shanghai film industry, down the Hong Kong, where he began working for Nanguo Film Company in 1948. He also lived in Bangkok for an extended period of time.

Overall, I’m really glad I went to the 10th edition of Midsummer in Teoswa. Hong Kong feels stifling sometimes, with strict censorship in place for any screening, leaving little room for creative and out-of-the-box programming. It’s exciting that good work is happening in China! And, apart from the films and community, I left with a strong feeling of belonging—they really make you feel like you’re coming home, even if you can only speak three words of the dialect and two of them denote different kinds of dumplings.

What’s New

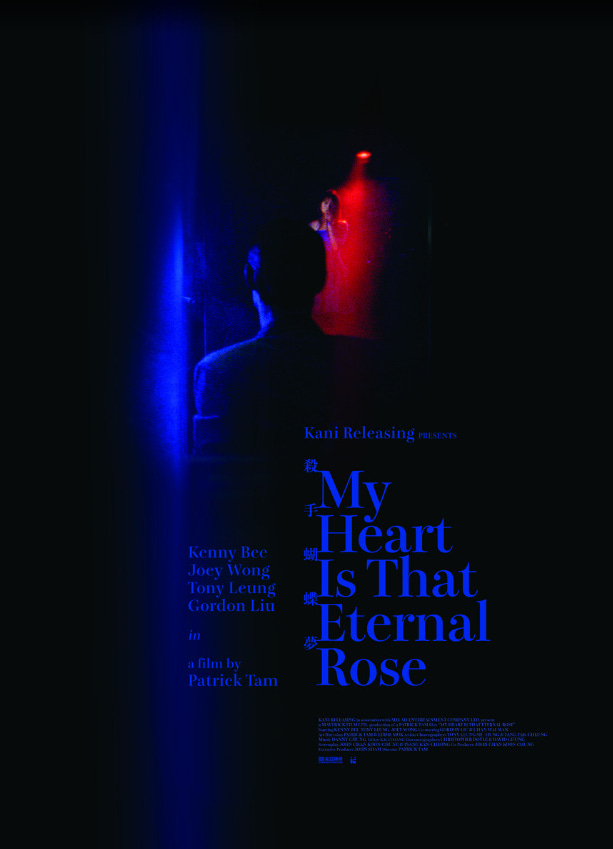

🍉 Beijing Watermelon is now on the Criterion Channel and 🌹 My Heart is That Eternal Rose will be joining it on August 1st

🍉 Beijing Watermelon has also just been released on Blu-ray, with a gorgeous watermelon slipcover by Qiu Jiongjiong and Leo Mak which sold out immediately. The regular edition (no slipcover, same otherwise) is headed for a reprint.

Upcoming Screenings

🍉 Beijing Watermelon - Saturday, July 27, 8:00 PM 10:15 PM at Spacy (Dallas, TX)

🍉 Beijing Watermelon - two at Suns Cinema (July 25 & 31) - SOLD OUT 🙇!

🌹 My Heart is That Eternal Rose is coming to The Cinematheque (Vancouver, BC) on August 4, 16, 29, and September 2. Audiences can take home this 11x17 posters 💗

🌹 My Heart is That Eternal Rose at Entre Film Center (Rio Grande Valley, TX) on August 23 & 24

🎥 📚

We caught a screening of Inside Out 2 on the occasion of our friend Jessica’s birthday. We met her because of Letterboxd, at a screening of Cageman. Give her a follow—she has a great LB account, rich with observations on Hong Kong cinema.

Ariel can’t put down Kim Stanley Robinson’s Aurora (2015). He says: “In typical late-KSR manner, it blossoms into less of a novel-novel, and more of a communicator’s tract: a methodical exploration of the hubris of the “generation ship” idea (and the notion that there might be a Planet B to save us all out there).”

Oh nice! Not sure how I found and followed Jessica on Letterboxd, but her observations are invaluable and without a trace of pretention.