Welcome to Shari

Our July release: Nao Yoshigai's experimental documentary/travelogue SHARI (2021).

The following is abridged from our booklet essay, included in our upcoming release of Shari.

To encounter the work of Nao Yoshigai for the first time is to encounter a novel way of thinking with images. At the convergence of documentary, choreography, ethnography, folk tale and fantasy, Yoshigai’s cinema is neither neatly experimental nor fully narrative. Instead, it is committed to the notion of perspective itself and, in the filmmaker’s own words, attempts to translate “what it feels like to be dancing, but on screen.”

Like dance, Yoshigai’s films often function as fantastical microcosms of mounting intensity, in which the rhythms and impulses of the body collide with those of the world around it. This, without fail, renders the world from a refreshing, animist point of view. Wood can be suddenly seen breathing, snow creaking, wind howling, sunshine blinding — it is all felt and embodied in Yoshigai’s images. Her films become an index of the small motions that make a life: pocket universes that are at once intriguing and always unsettling inasmuch as being alive is inevitably all these things, and more. […]

Commissioned by a city initiative, Yoshigai’s debut film Shari unfolds like a playful subversion of that very idea, focusing on the small town of the same name from a perspective that blends myth, performance and documentary once again.

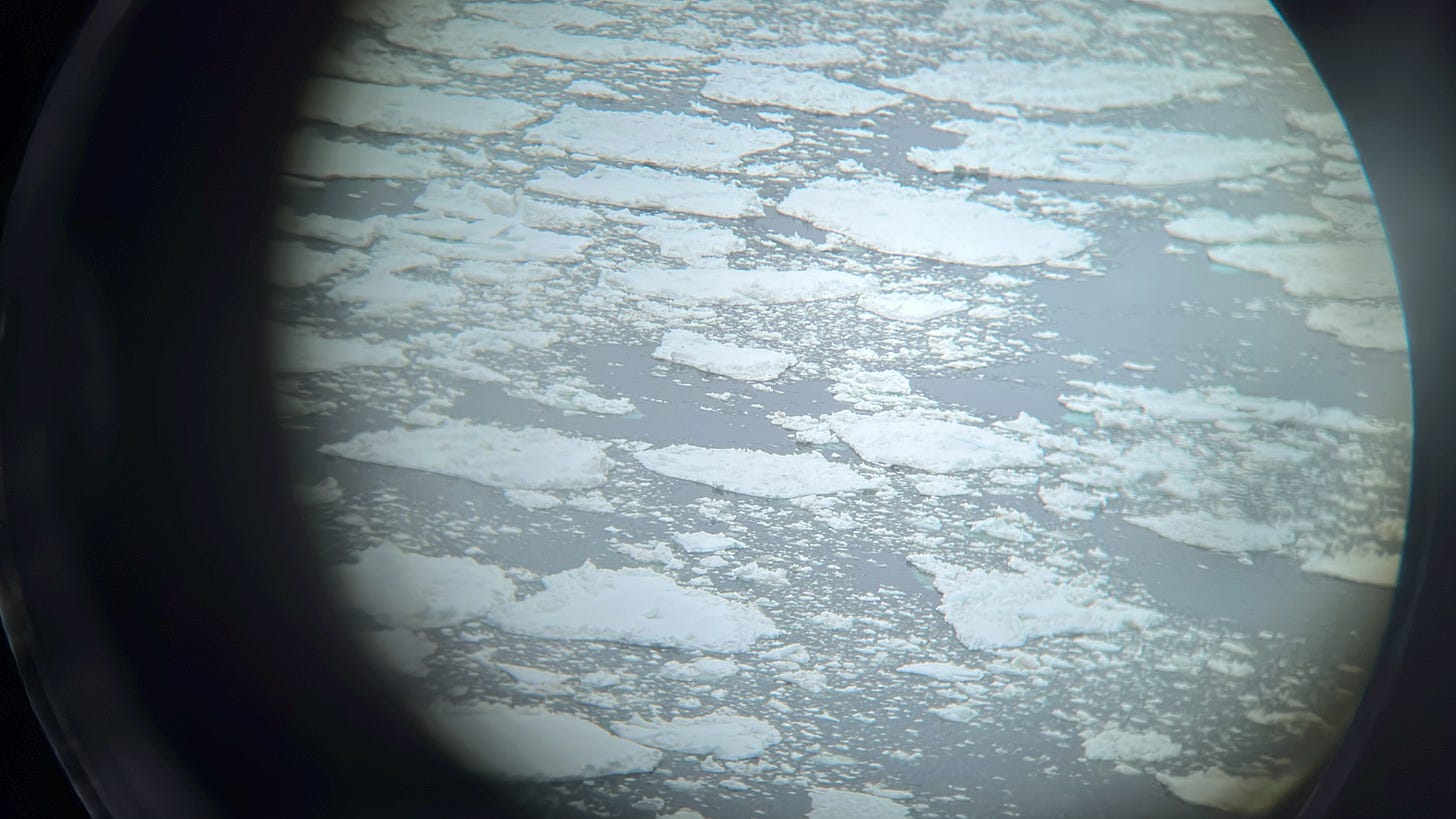

Shari is located on the north-east shores of Japan’s northernmost island of Hokkaido where the Sea of Okhotsk meets Russian shores. It is a very remote town of 11,000 people that survives off a strong tourism industry and fishing sector (where Japan’s best salmon is caught, say the locals). In the film, we meet hunters and bakers, fishermen and conservationists, interviewed casually (off-camera), while we are shown their lived-in spaces, “a reflection of their personality”. Shared by all is a concern for the area’s changing climate, as many of Yoshigai’s interlocutors speak of shorter winters, animals such as flying squirrels and deer, and the absence of drift ice – a local attraction that is also crucial to the salmon’s life-cycle.

What ties it all together and brings the film into the realm of fantasy is the presence of “the Red Thing”: a yeti-like creature “sanguine like a throbbing blood clot” that occasionally rampages through the scenery, eating offerings left by the film’s protagonists in fictitious sequences or terrorizing children in rowdy sumo matches. A yokai-like beast, The Red Thing haunts an otherwise pristine wilderness. […]

The Shiretoko Peninsula’s history, like much of that of Hokkaido, harkens back to Imperial Japan’s efforts in colonization. Settlement was incentivized by “free land” and the indigenous Ainu people were forcedly assimilated on the basis of the American model. To execute the annexation of Hokkaido, for example, the Japanese government hired Horace Capron, an agriculturalist best known for orchestrating the removal of Native Americans from Texas. Capron’s mandate included developing the area for agriculture, but Shari’s land proved unyielding and farms were eventually abandoned. Today, the land still hints at this scarring. Driving into Shari, one can see many young trees, planted in unnaturally straight lines on the periphery of snowed-in fields, in sharp contrast to the primordial forest that has been preserved a few miles away, at the Shiretoko National Park (the area’s main attraction and the organisation that keeps the region’s environmental history alive through various conservation and touristic efforts).

When we took a trip to Shari in March, 2025 in preparation for this release, the community that Yoshigai built when shooting the film welcomed us like old friends. It became clear that, today, in no small part due to projects like Yoshigai’s own film, the town is a very self-aware of its own history and unique cultural position, seemingly interested in reinventing itself beyond official histories and incentivized by a government keen on keeping the area’s economy active. Beyond the National Park, the Shiretoko Museum, which The Red Thing walks through in Shari, hosts an impressive collection of taxidermy and artefacts, while the Alp Museum houses paintings, prints and every single issue of Alp, a New Yorker-esque literary and mountaineering magazine that ran from 1958 to 1983 – and that became emblematic of a fascination with the region.

Other initiatives, such as Top End, a volunteer effort by the local community consisting of many of Shari’s subjects, invites artists and photographers such as Naoki Ishikawa (an acclaimed nature photographer and Shari’s director of photography) to visit every year. One of the result of the initiative is the publication Shiretoko Sustainable, a yearly “mook” (portmanteau of magazine and book), with a two-fold mission: introducing the region to tourists, and communicating how special Shari is to its own residents, so that they get involved in the community. It is at Ishikawa’s invitation that Yoshigai first came to Shari and first conceived of the film of the same name, with the support of the city.

When Shari was shot, the drift ice was not as plentiful as it was when we visited in early March of 2025. We were delighted, as was Nao most of all, at this lucky happenstance, or brief respite in the grim march of climate change. However, when we would mention the blessing of drift ice to the film’s subjects as we caught up with them, most still expressed concern about its dwindling amounts and its increasingly late arrival overall.

While The Red Thing sleeps its final sleep at the Sharicho Public Library, it became clear and heartening to us that the film had taken on a life of its own in the minds of the people who participated in it. We caught up with Kowada-san who now runs Secret Base, a beautiful cafe that offers delicious nabe lunches and the bread that can be glimpsed in Shari’s opening minutes. The Sakurais are still very focused on the Japanese pygmy squirrels living in their backyard, and offered us snacks and coffee.

Sitting down with Ito-san, the fisherman in the film, he was surprised it had only been 5 years since the film premiered. “I feel like it’s been 10 years,” he said, “so much has happened.” His concern for the environment and Shari’s fishing industry has only grown since, taking him to Youtube to further raise awareness about ocean trash collection and build his own brand of sustainable, locally-sourced salmon (available to purchase through vending machines in town). “But then I still package my salmon in plastic,” he said, suggesting the vicious cycle of making a livelihood from fishing practices.

Most surprising was meeting Koizumi Shunsuke over sushi: a 24-year-old fan of Shari who, compelled by the film’s portrait of the region and its community, packed his bags and moved to the city, taking advantage of Japan’s Regional Revitalization Program (that seeks to bring city folks back to deserted rural regions). He is now employed at a community center and café in Nakashari, where he helps promote the area’s activities.

On our final day in Shari, the sky was so clear we headed out to find a place to have a picnic between Mount Shari and Mount Unabetsu. We drove until we came across an inroad into a snowy field, where we could stop the car. We ate supermarket sashimi, the salmon, in fact all of it delicious, and reflected on our own contribution to this ongoing chain of awareness for Shari. How a government initiative to stop rural decline led to various artistic projects, including Yoshigai’s own film, how it led to people changing their lives around to be closer to nature. And how, now, by making the film more widely available, we may contribute in our own way, towards further placing Shari on the map. ⛰️

What’s Else Is New?

♨️ Directed by Lino Brocka launches on Criterion Channel featuring four of Brocka’s masterpieces, including our very own Bona and Cain at Abel!

📽️ Batang West Side, Desert of Namibia, Once a Moth, and What’s Up Connection are all in theatres, plus a special re-run of the fantastic Spacked Out at Metrograph this August. Stay up to date on our listings on our website here!

🚲 Fans of Japanese documentaries shouldn’t miss out on last month’s release, Tokyo Uber Blues, now shipping from Vinegar Syndrome with or without slipcover.

🧦 We’ve also launched out own online shop selling Kani merch; so far just our Classic Red socks, but more to come!

With love,

—Kani Releasing